I’m trying to make a commitment to learning and applying functional programming

somewhere in my practice. So yesterday I decided that I would invest the time

to try and “do something” in Elm…which I’d looked at, but never used.

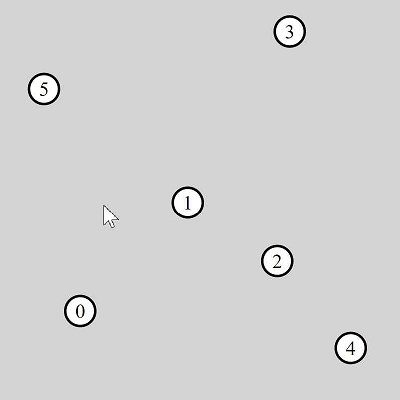

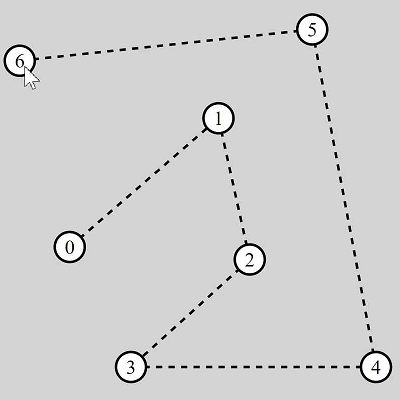

The goal I picked was to prototype an interface for editing an ordered set of

points in 2-D space. After many hours of poking and head-scratching, I managed

to get to a point where I had an SVG canvas you could click on to get numbered

dots connected with lines. Hopefully you can try it out below:

I thought I’d walk through my experiences, which may be illuminating for

others.

(Note: While there are some gotchas I hit that could use improvement, I want

to say up front that Evan & co. deserve recognition for Elm’s efforts.

Particularly notable in learning phases is what Elm has in terms of clear and

actionable error messages. The errors are the best I think I’ve seen in

any language, and it really makes a difference!)

Grokking the First Mouse Sample I Found

Usually when messing with languages I don’t know much about, I start from an

example that acts close to what I want. Since I was envisioning a program

with mouse movement and clicking, I went with the only mouse example

involving coordinates–(as opposed to button clicks)–on the “Try Elm” site.

https://elm-lang.org/examples/mouse

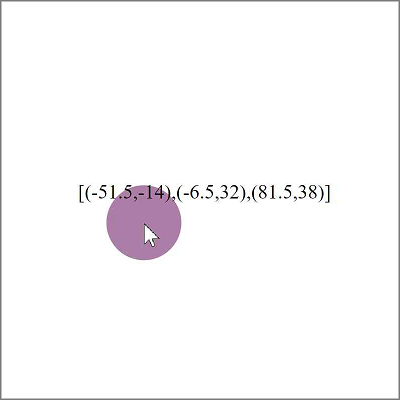

In the demo, you move a purple dot around. When you click it, the color

changes. On the surface, that seemed to have all the necessary events! I just

needed to be able to create some sort of “model” that gets updated each time

you click.

I noticed that the code was suspiciously short:

-- Draw a circle around the mouse. Change its color by pressing down.

--

-- Learn more about the playground here:

-- https://package.elm-lang.org/packages/evancz/elm-playground/latest/

--

import Playground exposing (..)

main =

game view update ()

view computer memory =

[ circle lightPurple 30

|> moveX computer.mouse.x

|> moveY computer.mouse.y

|> fade (if computer.mouse.down then 0.2 else 1)

]

update computer memory =

memory

Where should I add my contribution, to declare a List of points clicked?

How would I get the event notification of the actual moment that a click

occurred? 😕

The link in the comment didn’t provide any instantly gratifying help. It

spoke generally about how the playground lets you draw pictures and make

animations. Because I didn’t have the samples memorized, as far as I knew this

was just talking about the Svg and Div classes…and the URL was the

comment on all the files.

Turns out I’d incorrectly assumed that “Playground” referred to the general

set of interfaces that were shown in the simple demos on “Try Elm”. Such

try-online environments are often referred to as sandboxes or playgrounds, so I

did not realize that the Svg.circle and Html.div parts were the “real”

Elm…while things like Shape were “not”. Playground instead referred to

a restrictive set of templates for making fairly contrived samples.

One of those templates is called game. As a new reader of the language, you

can’t tell what’s being implicitly declared or what is predefined (compare

with also-lowercase computer and memory). Since it’s not qualified as

Playground.game, it does not jump off the page that those four letters are

where you should start your focus.

It turned out that reading code and comments for the playground itself was

more informative than the web pages. The type signature for the 3-argument

game function is:

game :

(Computer -> memory -> List Shape) -- arg #1: view function

-> (Computer -> memory -> memory) -- arg #2: update function

-> memory -- arg #3: initial memory state

-> Program () (Game memory) Msg -- return: signature main expects

What you’ll notice here is that the word memory is in lowercase. That makes

it a “type variable”. So basically, whatever type we pass in as an

initial memory value to the game function determines the type of the program

state. That constraint will then be forced to match in the related view and

update functions.

Thus we appear to be passing in () for the memory to Playground.game. It

means that this sample is only reflecting state out of the “computer”

abstraction–which the game is managing as part of its wholesale takeover of

our I/O interface.

That means this update function:

update computer memory =

memory

…is not just doing nothing at all…it can’t do anything. It might as well

be written as:

I’m sure this all might seem obvious to someone steeped in Elm. But that’s

presumably not who the samples are for! If you’re new, each of these findings

takes effort, so even short comments and definitions could go a long way.

For example:

initialMemory = () -- no memory in this sample

main =

Playground.game view update initialMemory -- delegate message processing

For The Sake of Argument: Using The Playground

The Playground is made to take over the whole viewport. If you look you will

see it only works in “Try Elm” because it uses a dreaded <iframe>. :-/

By assuming it controls the whole view, it ducks questions that are going to

be relevant for basically 100% of usages.

Clearly the Playground was going to be in the way for any “serious” use (even

if it was just “pretend-serious”, like something you might share embedded

in your blog!). But just to show we can once we understand it, here is the

playground sample modified to accrue state:

import Playground exposing (..)

initialMemory : { points : List ( Float, Float ) } -- clicked coordinates

initialMemory = { points = [] } -- start list empty

main =

Playground.game view update initialMemory -- delegate message pump

view computer memory = -- evaluates to a List of Playground.Shape

[ circle lightPurple 30 -- first shape is circle following mouse cursor

|> moveX computer.mouse.x

|> moveY computer.mouse.y

, words black (Debug.toString memory.points) -- second is points list

]

update computer memory = -- take in old points list and return a new one

if computer.mouse.click then -- one update call with true, per click

{ points = memory.points ++ [( computer.mouse.x, computer.mouse.y )] }

else

memory -- leave coordinate list unchanged

The purple circle still follows the mouse, but now you should get a textual

listing of clicked points in the middle of the screen. The words are after

the circle in the shape list, so they’ll be drawn on top of the circle

instead of behind it.

Having this work depends on the update function being called once-and-only

once with computer.mouse.click as true for each mouse click. It seems this

is the case.

Getting at the “Real” Events

Instead of Playground.game, I re-engineered main to leverage a lower-level

template. Rather than using Browser.document (which Playground builds on)

I decided to use Browser.element, so that it could be embedded into an

existing page.

This entry point takes four parameters instead of three. You have the freedom

to provide an initialization function, instead of just a starting memory state.

You can also give a list of “subscriptions” to events. Then your update is

parameterized with the specific triggering event.

So I looked at the list of subscriptions that Playground.game asks for:

gameSubscriptions : Sub Msg

gameSubscriptions =

Sub.batch

[ E.onResize Resized

, E.onKeyUp (D.map (KeyChanged False) (D.field "key" D.string))

, E.onKeyDown (D.map (KeyChanged True) (D.field "key" D.string))

, E.onAnimationFrame Tick

, E.onVisibilityChange VisibilityChanged

, E.onClick (D.succeed MouseClick)

, E.onMouseDown (D.succeed (MouseButton True))

, E.onMouseUp (D.succeed (MouseButton False))

, E.onMouseMove (D.map2 MouseMove (D.field "pageX" D.float) (D.field "pageY" D.float))

]

Seems like a reasonable list of capabilities. Browser.Events is imported

as E, so that explains the abbreviation. Then the D is for Json.Decode,

and…

…uh, wait, what? Why is JSON decoding involved in something as foundational

as mouse events? It’s as if the base system is passing the buck on the

question of how to model JavaScript events in Elm.

Should an event be translated into something with individual X and Y fields for

coordinates (like the JavaScript object does)? Or should coordinates be

wrapped in records with X and Y fields? Or perhaps Tuples of Floats, or Tuples

of Ints? Every Elm program might choose its own path, making sharing of code

more difficult.

But there’s an efficiency angle to it. You’re registering a decoding function,

and it extracts only the parts you are interested in out of the message. That

saves time in parsing and space in the resulting values.

Either way, we don’t really want a “global” subscription like this for

handling mouse clicks. If we’re going to be putting our element on a page

with other things we generally only want clicks on our element. So instead of

using Browser.Events we thus want to use Html.Events (though they work with

decoders in a similar way).

Another nuance is that we want the relative offsetX and offsetY coordinates

so our clicks will be ( 0, 0 ) in the upper-left hand corner.

The MouseMove extraction from the Playground above uses pageX and pageY.

If we didn’t do the right extractions during message decoding, it would be

really difficult to do DOM-relative adjustments after the fact. (Making DOM

calls is forbidden in purely functional code.)

Taking Off The Training Wheels

Subscriptions are an abstraction step away from callbacks. Things like

E.onMouseDown are subscription generators. On the JavaScript side there

are events happening that manifest as JS Objects–not Elm records. So you pass

the E.onXXX generator a function that can decode JSON into Elm messages, and

it wraps that function to hand back as a Sub. Then if such an event happens

the decoder is called to make an Elm Msg to pass to update.

The Playground’s translations are fairly lazy. Those D.succeed invocations

make JSON decoders that actually ignore the JSON entirely…returning a fixed

value. So an onClick event is turned into the event MouseClick without

extracting anything about coordinates, or modifier keys. Only MouseMove is

processed into anything other than an indication of “the event happened”.

Here is the mouse click example expanded out, so it no longer uses the

Playground and has direct access to the messages. For brevity, it punts

on some viewport management issues (scaling/resizing), and the purple circle is

omitted. I also tried not to hide teachable details…by fully qualifying

where each definition is coming from.

You can copy-paste it into the “Try Elm” site, and it should work (at

least as of Elm 0.19).

module Main exposing (..) -- "Try Elm" doesn't need, but compiler does

import Browser -- contains templates for making Browser-based `main`

import Json.Decode as JsonD -- most JavaScript events come to Elm as JSON

import Html.Attributes as HtmlA -- used for `style:` attribute

import Html.Events as HtmlE -- subscribe to HTML element events via `on`

import Svg -- our `view` function makes list of SVG elements

import Svg.Attributes as SvgA -- all SVG property fields (x, y, color...)

type Msg -- type for Elm-digested forms of the Javascript events

= MouseClickMsg ( Float, Float )

| NoMsg -- add more events here

type alias Memory = { points: List ( Float, Float ) } -- clicked points

initialMemory : Memory

initialMemory = { points = [] } -- start list empty

main = -- drop `Browser.element` parameters to simplify view/update/etc.

let

init : () -> ( Memory, Cmd Msg ) -- flags must declare type for safety

init flags = ( initialMemory, Cmd.none )

in

Browser.element -- establish message pump

{ init = init

, view = view

, update = \msg memory -> ( update msg memory, Cmd.none )

, subscriptions = \memory -> Sub.none

}

decodeClick = -- use lambda to pack the two parsed fields into a Tuple

JsonD.map2 (\a b -> MouseClickMsg ( a, b ))

(JsonD.field "offsetX" JsonD.float)

(JsonD.field "offsetY" JsonD.float)

view memory = -- renders memory state into an HTML element

Svg.svg

[ HtmlA.style "background" "lightGray"

, SvgA.width "400" -- could improve via BrowserE.onResize

, SvgA.height "400" -- (use of SvgA.viewBox complicates mouse points)

, HtmlE.on "click" decodeClick -- extracts offsetX/Y to make message

]

[ Svg.text_ -- note: `text_` not `text` for the SVG node proper

[ SvgA.fill "black"

, SvgA.x "200"

, SvgA.y "200"

, SvgA.textAnchor "middle"

, SvgA.dominantBaseline "central"

]

[ Svg.text (Debug.toString memory.points) -- `text` for node content

]

]

update msg memory = -- take in old points list and return a new one

case msg of

MouseClickMsg offsetPos ->

{ points = memory.points ++ [offsetPos] } -- new list w/new point

_ -> memory -- leave coordinate list unchanged

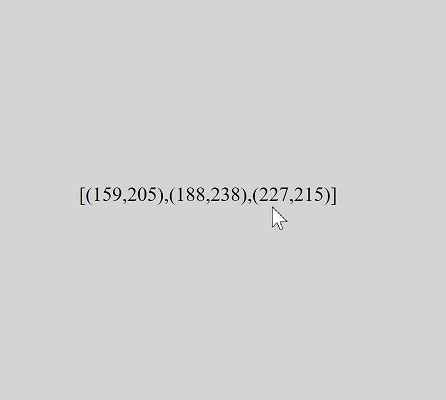

Since I didn’t involve viewport handling, I colored the SVG canvas gray so

it would be clear where the clickable area was.

Drawing Dots Instead of Printing Debug Text

It would be a little sad if this article stopped there, so let’s evolve the

code into the numbered circles and lines shown at the beginning.

We’ll start by factoring out our ugly debug rendering into its own function.

This way we know exactly what we’re replacing, and can see its type signature:

view memory = -- renders memory state into an HTML element

Svg.svg

[ HtmlA.style "background" "lightGray"

, SvgA.width "400"

, SvgA.height "400"

, HtmlE.on "click" decodeClick

]

(renderDots memory.points)

renderDots : List ( Float, Float ) -> List (Svg.Svg msg)

renderDots points =

[ Svg.text_

[ SvgA.fill "black"

, SvgA.x "200"

, SvgA.y "200"

, SvgA.textAnchor "middle"

, SvgA.dominantBaseline "central"

]

[ Svg.text (Debug.toString points)

]

]

Breaking the function out shouldn’t change the behavior. It just shows we need

a new renderDots that makes a list of circles at each coordinate, instead of

a list containing just one text blob. The elements in this list will be

(Svg.Svg msg).

(Note: When parentheses contain a comma they are a tuple and when they don’t

they are just being used for grouping. To help make this difference pop of

the page more, the Elm style guide suggests that Tuples be spaced out from

their delimiters. It’s not enforced, but seems to be good practice.)

Now let’s put our functional programming 101 knowledge to use, and make a list

of Svg.circle from a coordiate pair list with List.map!

renderDots : List ( Float, Float ) -> List (Svg.Svg msg)

renderDots points =

let

oneDot : ( Float, Float ) -> (Svg.Svg msg)

oneDot ( x, y ) =

Svg.circle

[ SvgA.r "12" -- Note: `r`, not `radius`

, SvgA.cx (String.fromFloat x) -- Note: `cx` for center, not `x`!

, SvgA.cy (String.fromFloat y) -- Note: `cy` for center, not `y`!

, SvgA.fill "white"

, SvgA.stroke "black"

, SvgA.strokeWidth "2"

]

[] -- this circle node has no contents, just attributes

in

List.map oneDot points

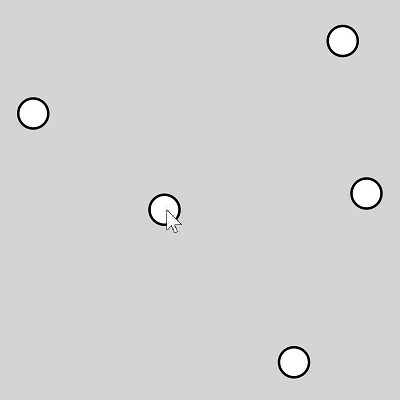

And behold, dots when you click!

(Note: It’s somewhat unsettling that map is not generic. If you’re

mapping over the elements in a List, you have to use List.map. If it’s a

dictionary–e.g. Dict–you have to use Dict.map. More on this later.)

Numbering Our Dots

The order is implicit from the list, which means it’s not available as a

data member during List.map. We’ll need a way of getting the running index.

If that is all we want, we are lucky, because there is a List.indexedMap.

But if each dot makes both a circle AND a text element, our oneDot will now

be producing multiple (Svg.Svg msg). So we’ll have to update the type

ignature to a list, and concat the results for each dot to make a flattened

list of same-type elements.

renderDots : List ( Float, Float ) -> List (Svg.Svg msg)

renderDots points =

let

oneDot : Int -> ( Float, Float ) -> List (Svg.Svg msg) -- now a list

oneDot index ( x, y ) =

[ Svg.circle

[ SvgA.r "12"

, SvgA.cx (String.fromFloat x)

, SvgA.cy (String.fromFloat y)

, SvgA.fill "white"

, SvgA.stroke "black"

, SvgA.strokeWidth "2"

]

[]

, Svg.text_ -- notice again the drawing element is `text_`

[ SvgA.x (String.fromFloat x)

, SvgA.y (String.fromFloat y)

, SvgA.fill "black"

, SvgA.textAnchor "middle"

, SvgA.dominantBaseline "central"

]

[ Svg.text (String.fromInt index) -- node content is a `text`

]

]

in

List.concat (List.indexedMap oneDot points)

And presto… numbers!

Connecting Dots With Lines

It was lucky to find List.indexedMap that could keep some state between

individual calls to the oneDot. But what if we couldn’t find the function

we needed? Drawing lines requires knowing adjacent elements. Is there a

general solution if you need something more?

Well…the truly general solution is “learn how to write functions in a

functional programming language!” So let’s think about drawing lines. If we

have N dots we want to draw (N - 1) lines. We can write a case

statement in Elm that looks like a solution from the early chapters of a

functional programming textbook:

renderLines points =

case points of

[] ->

[] -- no points, no line

[_] ->

[] -- one point, no lines

x::y::rest ->

(oneLine x y) :: (renderLines (y::rest)) -- recurse each pair

The main thing to note here is that :: is Elm’s equivalent of : in Haskell.

The item on the left is always a single element, which should match the type

of the elements in the list on the right.

All we need to do is add the definition of oneLine and it’s ready:

renderLines : List ( Float, Float ) -> List (Svg.Svg msg)

renderLines points =

let

oneLine : ( Float, Float ) -> ( Float, Float ) -> (Svg.Svg msg)

oneLine ( x1, y1 ) ( x2, y2 ) =

Svg.line

[ SvgA.x1 (String.fromFloat x1)

, SvgA.y1 (String.fromFloat y1)

, SvgA.x2 (String.fromFloat x2)

, SvgA.y2 (String.fromFloat y2)

, SvgA.stroke "black"

, SvgA.strokeWidth "2"

, SvgA.strokeDasharray "5 5"

]

[]

in

case points of

[] ->

[] -- no points, no line

[_] ->

[] -- one point, no lines

x::y::rest ->

(oneLine x y) :: (renderLines (y::rest)) -- recurse each pair

All that’s left to do is prepend the lines to the dots in our view function.

(We put the lines first, so the dots draw on top of them.)

((renderLines memory.points) ++ (renderDots memory.points))

And there you have it. Clicks, dots, numbers, and lines!

An Alternative Way: Event Helper Modules

I wanted to get my case to work using base Elm, without installing any user

modules. This means you can build them without needing to elm install any

files into your elm.json. Also, all the code can run on the “Try Elm” site.

But there are modules from the community that take care of some of the

boilerplate work for you. When it comes to mouse events, there is a library

elm-pointer-events…which also covers Wheel, Drag ‘n’ Drop, Touch, and more

abstracted “Pointer” messages:

https://package.elm-lang.org/packages/mpizenberg/elm-pointer-events/latest/

Earlier I mentioned that some fragmentation might happen with different

standards for choices in things like how coordinates were represented. To make

things smoother, I followed elm-pointer-events choice for using tuples and

the name offsetPos. I looked it up in their Decode.elm file, where

you can see that they’re extracting several fields…whether you plan to use

them or not.

A similar helper called elm-keyboard-event works out the details of key

presses. There’s a nice demo here of the module which shows the source on the

right, and event properties as you press them:

https://gizra.github.io/elm-keyboard-event/Document.html

Conclusion

Once I got started with it, Elm did not feel hard to grasp. Strangely, the

“easy” examples on the “Try Elm” site were the part that threw me off the

most. Something about their presentation created a barrier to being able to

contextualize just what it was that I was looking at.

I can empathize with why the playground examples are included. They are

actually a fairly sophisticated demonstration of abstracting away application

structure. It’s in a style that would be difficult in many other languages.

But the purple dot example–with no user state and deliberately unused

parameters–really just added confusion for me. The lack of type signatures

and comments turned it into a cryptic puzzle to be solved about advanced

abstraction features, as opposed to an “easy” example for teaching! And

once the puzzle was solved, I found I had to throw it all out…which makes

me feel the Playground is a bad entry point.

I’ve gathered from reading that the language core may be weak in some key

areas. The only thing that caught my attention in writing the code for this

example was the lack of a generic map operation. That seems like a big

deal, though it was not much of one here. So I’m not sure how many of the

complaints are academic vs. being significant in practice for the kinds of

problems Elm is solving.

Overall, the experience leaves me with a largely positive impression of the

project. It may not be “the” functional answer of the future, but it looks

like it’s empowered some projects to get closer and pushed the state of the

art…and raising the bar on error messages, like I mentioned. So finally

trying it out feels like time well spent!